[Issue #4] Eyes Wide Always [Series Issue #1]

A layman's exploration into the physiology and neurobiology of PTSD: Hypervigilance

“Even rest is fragile. I am afraid all the time. I am afraid of what has already happened. And of what could happen.”

-Edith Eva Eger, The Choice: Embrace the Possible

This week, we’re kicking off a new thematically curated series of newsletter issues-the theme? Physiology and neurobiology of trauma and PTSD.

Questions? Thoughts? Comment below or send me an email: bcpurchas@gmail.com

Remember when we explored the history of PTSD and Herodotus penned his experiences from the Battle of Marathon? A soldier went blind from the trauma of war, though he was not injured in any way, and other soldiers had to be called off from the fighting due to exhaustion. There are several other manifestations of PTSD, one of which is the always-present hypervigilance.

Hypervigilance, or “waiting for the other shoe to drop”, defined by Merriam-Webster, is “Extreme or excessive vigilance : the state of being highly or abnormally alert to potential danger or threats.”

And they further expound with examples: “a person suffering from PTSD may have sleep disturbances, irritability, hypervigilance, heightened startle responses and flashbacks of the original trauma.”— Ellen L. Bassuk et al.

“One common trait among fearful fliers is hypervigilance; they often spend the entire trip watching the flight attendants, analyzing the chime system, and assessing the sounds of the engines.” —Nancy J. Perry et al.

It’s safe to say I’m a fearful flier. I tend to have panic attacks inside airports and my wonderful wife helps stave off a total meltdown with a lot of hand holding, hugs, and empathy. Maybe if, collectively, we had a better understanding of what’s transpiring when someone’s having an epic meltdown, we can find the compassion and empathy to offer kindness instead of judgment. The symptoms of my PTSD and the hypervigilance, in particular, have made it quite difficult to do many things alone or with people. You read that right.

I knew I was a fearful flier before reading the above definition. The engine noise, the turbulence, any weather (other than dry and sunny) trips the anxiety that seems to be hardwired into my system. I study the faces of passengers, usually kids if there are any, for signs of fear. My palms get sweaty and I wipe them down on my pant leg. My heartbeat is hard to feel because the swelling of my anxious thinking blows out any space left for regular rhythm. My pupils are constantly dilated to the point where, even when I’m not stoned as shit from weed, I look like I might be. For a long time, I thought that was a natural thing for me. It’s not. It’s protective. How?

By definition, hypervigilance is about threat assessment, in any environment.

Hypervigilance is a blatant manifestation of the twisted and misshapen perspective on reality. My pupils are constantly dilated because I’m continually looking for threats. Hypervigilance occurs out of fear, self-protection, and survival. It’s not like I wake up everyday saying, “I really fucking hope I’m extra hypervigilant today.” But everyday comes and it feels like everyday, I’m extra hypervigilant. Feels like an oxymoron.

Recently, a good friend of mine and I were chatting. We were inside the safety of the place I call “home” - my wife and I live fairly close to a somewhat busy airport and hear all kinds of noises from the sky above. This particular day, my friend and I were standing around and the tornado sirens started to blast - they always do around 11am on a Wednesday and yet, both of us stopped talking, opened our ears, and locked eyes. We had the same thoughts in the same pattern, which were:

Was that loud ringing noise my tinnitus?

Nope, it wasn’t the tinnitus, so it must be a threat

What kind of threat? Life-threatening! Panic!

Yell out “get down” for the safety of everyone involved

This time, we were both able to catch each other at number 3 and we barely missed the part where we hit the deck. Then we laughed manically about how triggering that was and know we both had a very similar experience (and small aside - this experience is what drove me to do this themed series).

If we dig into these examples a bit more, we can begin to understand and accept the hypervigilance we may experience day-to-day.

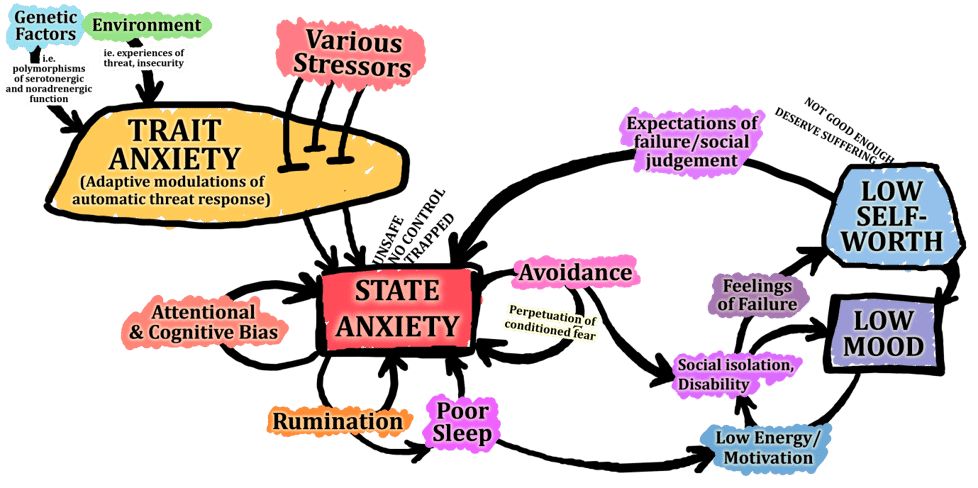

This image, taken from Real Depression Project, illustrates the complexities of PTSD and neurobiology.

Back in 2013, Matthew Kimble, et al. did a study on hypervigilance and what’s known as the ‘forward feedback loop’. Essentially, a forward feedback loop is an input leading to an output.

The study, “The Impact of Hypervigilance: Evidence for a Forward Feedback Loop” illustrates hypervigilance in a way that’s easy to digest and understand. A few prominent things from the study stand out for our purposes here, one of which is how our attention is deeply affected by our trauma.

“A number of prominent theories suggest that hypervigilance and attentional bias play a central role in anxiety disorders and PTSD. It is argued that hypervigilance may focus attention on potential threats and precipitate or maintain a forward feedback loop in which anxiety is increased.”

If we take this information and utilize generic photographs to help understand hypervigilance, we get a much better handle on the manifestation of anxiety, PTSD, and trauma. In the interest of time and energy, let’s use the same photo the study above used, inside a New York City subway station, with a grid laid over.

The grid helps us break down the scene. Imagine standing on the platform. It’s a Thursday morning and you’re just about to enjoy the newest issue of I’m Not Triggered. The cool air is dry, the concrete is drab, and the long yellow line tells you where you should not stand (see that guy on the yellow?) My brain immediately wanted to yell at him to step away from the yellow line, out of fear of something terrible happening to him. I have no idea what you see in the photo, but I can tell you what my trauma-infused neurons reported to my head - I know the exit is forward, thanks to the giant sign and that gives me immediate relief. I would probably next try to find the actual exit, just to know where it’s located. I see what might be some construction happening on the other side of the tracks. I see a man in a white hat and no one else seems to be wearing a cap, so he stands out to me as a possible threat (he’s the “other” in this situation). Then I see a young college aged guy looking at the dude in the yellow zone (not just me!) and I’m sure I’d hear a lot of random bits of conversation, the subway cars rumbling past as they pick up and drop off. I’d hear the squeak of brakes and the dusty noise of the subway car doors opening, then the chime as people flood off and then on, lining the same subway car.

Let’s imagine we only waited on the platform for 3 minutes. By the time those 180 seconds tick by, my anxious and hypervigilant brain has taken stock of a lot of terrible shit that could go wrong and of my potential threatening environment -

Does that college aged guy have a gun in his bag?

Is that man going to jump in front of the subway or fall off and get his legs maimed?

How many people are behind me and what are they doing?

What are the chances I’ll be stabbed in the ribs?

My hypervigilance comes out in all sorts of ways. My wife walks into a room and if I don’t see her before she says “hi babe,” I freak the fuck out. It’s terrifying. Loud noises, like the dogs barking at a fucking squirrel outside the window, are also terrifying. Hence, this is part of why I’m a fearful flier. I have a very low threshold for too loud or too many noises at one time. It’s difficult for me to take naps because I feel vulnerable and unprotected while the rest of the world seems to be active and able to infiltrate my home in the safe suburbs of the Midwest. I have a hard time driving far distances on city or local roads (I do better on less busy highways and streets.) Standing in a checkout line breeds a level of anxiety so anti-social, the steam of which evaporates into a vapor cloud filled with frustration and “fuck this”-ness.

I guess I could decide not to fly. Not to go to the store. On the subway. Hell, the easiest thing to do would be to stay here, at home, inside my womb. At least I wouldn’t be battling the constant pings and comms of my terrified inner child. But those decisions don’t feel like the right ones. Not for me.

I dream of living a life based around travel. Seeing countries, cities, experiencing new things with the people I love so dearly. I dream of touring for my writing career (maybe this Substack newsletter will completely take off?) I dream of Colorado hikes and mountains, Spanish music on a little patio, waterfall climbing in Jamaica.

But, daily life is about getting to and from places, with a majority of my own autonomy and ability still intact. Daily life is about making dinner, doing laundry, completing a shit ton of house projects, and planning trips to see friends a few states away.

I don’t want my PTSD, my anxiety, and especially my hypervigilance to deter me from living a fulfilling life. I want to be able to navigate a happy life. Learning how, while systematically entrenched in not destroying everything I have and love is one of my bucket list items.

I’m learning maybe I can use my hypervigilant brain for good. Maybe something I write here will positively impact you. For me, that’s more than plenty.

Keep an eye out for next week’s thematic issue - the interchange and link between PTSD and addiction. If you liked this issue, share it with a friend!

I share the flying anxiety. Comes from a near-crash in the Himalayas that I never totally got over. I am hyper aware of every change of engine noise and vibration.

I share your dreams, minus the scaling a waterfall :) My husband and I want to go to Tigers Nest in Bhutan at some point.

I believe that your substack will grow and grow! There are so many that need what you are offering.