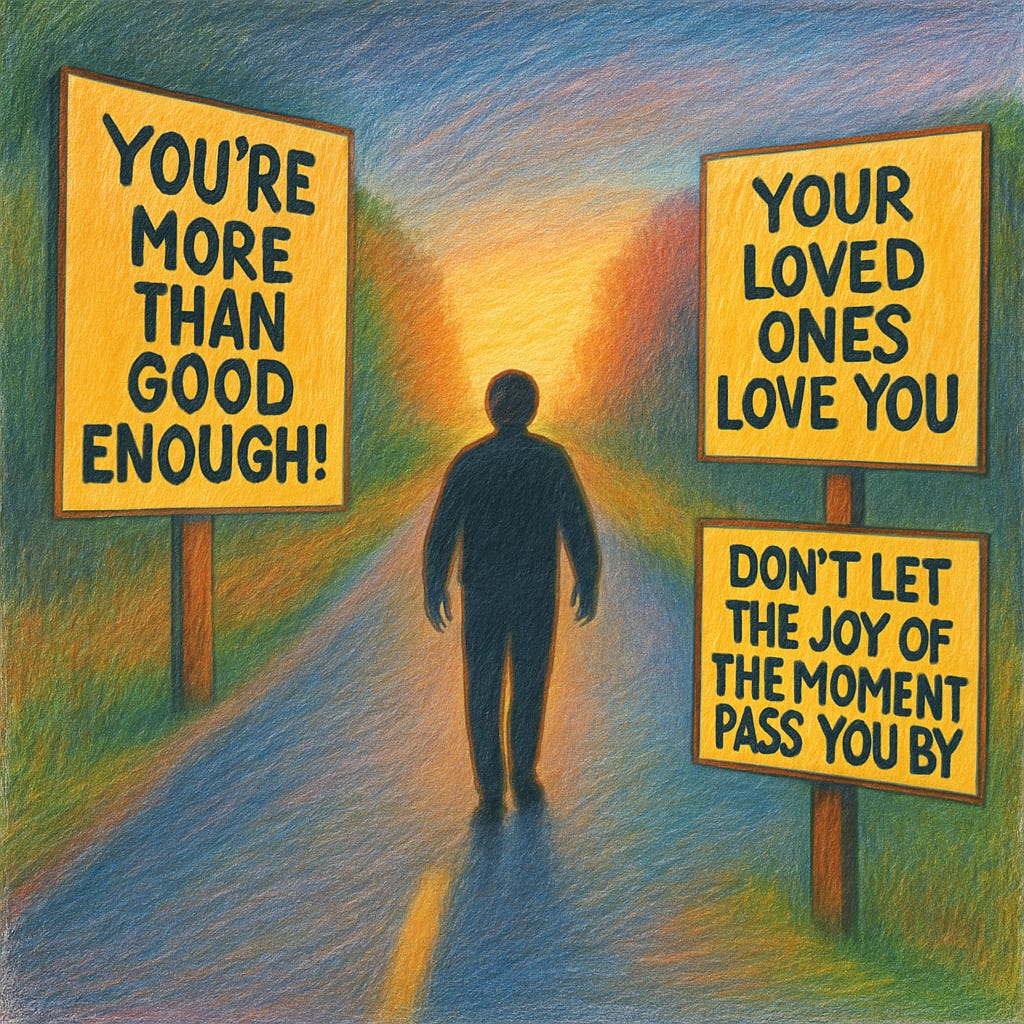

[Issue #46] Am I Not Enough?

An exploration on internal negative beliefs and why they're hard to change

I’m Not Triggered is on YouTube! Watch this episode on YouTube here

We all carry stories about ourselves—internalized myths born from past experiences and trauma. For years, I lived by these myths, from believing that showing emotion made me weak to thinking I had to handle my pain alone. These narratives were powerful but misleading - and they got me into relationships with people who were abusive and unhealthy. But, how does one find themselves in a place of wondering what our inherent value is?

Myth 1: “Showing Emotion Is a Sign of Weakness”

I was taught from a young age to hold it together.

If I cried or showed fear, I was told to “be strong” or, “blow your nose, straighten your clothes, and move on”, or “you’re too sensitive.”

Over time, I internalized the belief that expressing emotions meant I was weak, and showing emotion likely netted me the exact kind of attention I desperately craved.

Like many trauma survivors, I learned to bury feelings of sadness and hurt. Outwardly, I appeared “fine,” (fun fact: in Al-Anon we’ve created meaning from the word as an acronym to now be “fucked up, insecure, neurotic, and emotional”) but inside, the unexpressed grief and anger metastasized into a lonesome and emotional cancer. I felt isolated behind a mask of stoicism, convinced that if I let my true feelings show, I’d be judged, or worse, rejected.

It’s taken me a long time to learn that emotional expression is not weakness – it’s humanity. Far from protecting us, constantly suppressing emotions can backfire. Research in Health Psychology Review found that people who habitually suppress their emotions experience increased stress on their bodies, as evidenced by elevated heart rate, blood pressure, and stress hormones.

In other words, hiding pain doesn’t make it go away; it intensifies stress internally. Over time, this can harm both mental and physical health. Moreover, by numbing “negative” feelings (though, “negative” and “positive” feelings are only labelled this way by our judgement because all emotions are equal), we also blunt the positive ones.

A meta-analysis in the Clinical Psychology Review (Fernandes & Tone, 2021) – “A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between expressive suppression and positive affect” – showed that greater emotional suppression correlates with significantly lower positive emotions in daily life In short, shutting down sadness also shuts down joy. Real strength isn’t silent endurance; it’s the courage to express what we feel in healthy ways. When I learned to safely share my emotions – through therapy, journaling, even tearful conversations with friends – I found relief and connection. The myth of “weakness” began to unravel. I wasn’t weak for feeling; I was simply human.

Myth 2: “I Must Be Perfect to Be Worthy”

On the surface, being a perfectionist sounds positive – who doesn’t want to do well? But for me, perfectionism was a shield. If I never made a mistake, maybe I’d never be hurt or criticized. After trauma, I clung to the idea that I had to be flawlessly good: never upset anyone, never fail at anything. Any slip-up, even a minor one, sent me into a spiral of shame. I felt that my worth depended entirely on my achievements and doing everything “right.” This myth kept me anxious and exhausted. No matter how hard I tried, “perfect” was never attainable, and I constantly felt not good enough.

Perfectionism doesn’t protect us; it harms us. Psychologists now understand that perfectionism is a double-edged sword – especially the self-punishing, critical kind. A recent meta-analysis published in Cognitive Behavior Therapy titled “The relationships between perfectionism and symptoms of depression, anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis” found that the self-critical side of perfectionism (known as perfectionistic concerns) has a strong link to mental health problems:

”Perfectionistic concerns had significant medium correlations with anxiety, OCD and depressive symptoms…Results demonstrate perfectionistic concerns have a stronger relationship with psychological distress than perfectionistic strivings, but strivings are significantly related to distress.”

In that analysis of over 113,000 people, higher perfectionistic concerns were moderately to strongly correlated with greater depression, anxiety and OCD symptoms . In contrast, the healthier striving for improvement showed only small associations with distress. These findings confirm what my lived experience taught me: constant self-judgment and fear of flaws fuel anxiety and erode self-worth. Striving for growth is fine, but expecting perfection is a recipe for burnout (and worse, self-harm urges and other nasty effects).

I began to replace “I must be perfect or I’m nothing” with “I am enough, even with my imperfections.” Ironically, when I allowed myself room to be human – to make mistakes and learn – I became more productive and much kinder to myself. My worth isn’t defined by an error-free report card; I am worthy just as I am, work-in-progress and all.

Myth 3: “If I Really Were Strong, I Would Handle This Alone”

Trauma made me feel isolated. I believed that asking for help would burden others or reveal my own weakness. So I didn’t talk about my panic attacks or nightmares. I forced a smile and kept everything to myself, even as I was drowning inside. This myth – that real strength means never needing anyone – was reinforced by societal messages like “pull yourself up by your bootstraps.” I felt that to be “okay,” I should be entirely self-sufficient. Admitting I needed therapy or support seemed like confessing failure. As a result, I suffered in silence much longer than I needed to.

True strength isn’t solitary. Humans are social beings, and reaching out for support is a courageous, not cowardly, act.

In fact, research shows that one of the biggest barriers to seeking help is the stigma we attach to it. A comprehensive review in Psychological Medicine (2014) titled “What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies” found that internalized stigma and fear of judgment significantly discourage people from getting help;

“Stigma was the fourth highest ranked barrier to help-seeking, with disclosure concerns the most commonly reported stigma barrier. A detailed conceptual model was derived that describes the processes contributing to, and counteracting, the deterrent effect of stigma on help-seeking. Ethnic minorities, youth, men and those in military and health professions were disproportionately deterred by stigma.”

Across 90,000 participants, stigma had a small-to-moderate negative effect on help-seeking – meaning many who need support don’t reach out because of shame or the myth that they “should” do it alone.

I saw myself in those numbers. But I also learned another crucial truth: getting help works. Social and professional support can be life-changing. A meta-analysis in Clinical Psychology Review (Wang et al.) in “Social support and posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies” demonstrated that people with strong social support tend to have lower PTSD symptoms over time In that analysis of over 30,000 trauma survivors, higher support predicted modestly reduced PTSD symptoms later on.

In other words, letting others in can actually help heal our wounds. I remember the terror of walking into my first support group meeting, ready to bolt. But instead of judgment, I found understanding. Over time, therapy and peer support taught me that asking for help is not a sign of weakness – it’s a step toward healing. None of us should have to carry pain alone.

Myth 4: “My Trauma Defines Me”

For a long time, I didn’t know who I was beyond my pain. Trauma can consume your identity – you start to think of yourself as broken, a victim, or as nothing more than your depression, anxiety, or diagnosis. I used to say “I am depressed,” as if it were all of me. In the aftermath of my trauma, I felt I’d never be anything but that frightened, hurt person. This myth told me that my past had permanently ruined me, that every aspect of my identity and future was defined by what I had been through. It was a heavy, hopeless feeling – as if the story of me had been written in tragedy and I had no power to change it.

You are more than what happened to you.

Trauma influences us, but it does not have to define our entire identity. In truth, many people find that over time – and with healing – they grow in unexpected ways. Psychologists call this post-traumatic growth. In fact, a systematic review and meta-analysis in the Journal of Affective Disorders reported that nearly half of trauma survivors experience moderate to high post-traumatic growth – significant positive changes in their life perspective, sense of self, or relationships – after enduring trauma. This 2019 study (“The prevalence of moderate-to-high posttraumatic growth: a systematic review and meta-analysis”) looked at dozens of studies and found about 52% of survivors eventually saw meaningful personal growth emerge from their struggles.

Such growth might mean a new appreciation for life, discovering inner strength, or redefining one’s purpose. Hearing this research the first time, I was skeptical – what “growth” could ever come from my pain? But as I healed, I noticed changes: I became more empathetic, I prioritized what really matters to me, and I learned I could survive deep sorrow and still find joy. My trauma is part of my story, but it is not the whole story. We each have the power to author new chapters. Therapies like narrative therapy or cognitive processing therapy often focus on helping people rewrite their personal narrative – to move from seeing themselves as “nothing but a victim” to recognizing themselves as a survivor with strengths and a future. I started literally writing a new narrative of who I am: yes, I have scars and memories of trauma, but I am also a friend, a parent, a creative soul, a resilient and multifaceted person. Our identities are expansive, and we get to reclaim them from the shadow of trauma.

Myth 5: “I Should Be Ashamed of What I’ve Been Through”

Shame is a stealthy, cancerous monster. In my case, I wasn’t even aware how much shame I carried until I tried to speak about my trauma. I felt ashamed that I was “damaged,” ashamed of the things that were done to me, and ashamed of how I coped (or struggled to cope), and how I’d externally manifested my internal shame. This of being ashamed of ourselves and experiences is a quiet one. This myth whispers that it was your fault or that we’re somehow dirty, weak, or “less than” because of our suffering.

The weight of unspoken shame was crushing—it kept me from seeking comfort and drove me deeper into self-loathing. I believed if people knew “the real me,” with all my trauma and pain, they wouldn’t want me.

The truth is - shame belongs to the perpetrator, not the survivor.

What happened to you is not your fault, and your feelings and reactions are normal responses to abnormal events. Far from being a personal failing, feeling shame after trauma is incredibly common – but it’s something we can overcome. A 2019 meta-analysis in the Journal of Traumatic Stress titled “Association Between Shame and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Meta-Analysis” found that shame is widely present among trauma survivors and moderately associated with the severity of PTSD symptoms. In that study, individuals with intense trauma-related shame tended to have much higher PTSD symptoms – a testament to how deeply shame can wound us. Importantly, the authors noted that addressing shame is crucial for healing: treating shame directly (for example, by challenging those self-blaming beliefs in therapy) can improve trauma recovery.

This insight became a turning point in my own journey. When I finally opened up to a trauma-informed therapist, she helped me see that the shame I carried never rightfully belonged to me. I began to talk back to that myth: I survived something terrible – I have nothing to be ashamed of. The wrong was done to me, not BY me. As I gradually let go of the shame, I felt lighter. Sharing my story with safe people, instead of hiding it, transformed that shame into connection and self-compassion. If you feel shame about your trauma or your mental health struggles, remember that your feelings are valid – but the negative beliefs behind that shame are deeply flawed myths. You did what you had to in order to survive. There is no shame in surviving. The more we speak about trauma openly, the more we strip shame of its power.

Beyond Myths

These five myths – about emotion, perfection, independence, identity, and shame – often feed on each other and keep us trapped. They’re fueled by past hurt and societal misconceptions, but we are not obligated to keep believing them.

Healing, for me, has been in large part an act of myth-busting: recognizing these internalized stories for what they are (falsehoods), and actively rewriting them with truth, self-compassion, and evidence. It’s not an overnight process. I still catch echoes of these myths in my mind from time to time. But now I have new narratives to replace them with.

Beyond the myths, here are the truths I hold onto: Feeling deeply is a sign of life, not weakness. I don’t have to be perfect to be loved or worthy – I am already enough. It’s brave to ask for help when I need it. I am defined by so much more than my pain. And no matter what I’ve been through, I deserve understanding, not shame. These are the stories that define me now.

In rewriting our personal myths, we take back power from our trauma. We honor the full complexity of who we are – not just our suffering, but our strength, our growth, and our inherent worth. If you’ve seen yourself in any of these myths, I invite you to challenge them. Ask whether that story is serving you, or keeping you small. Seek out the knowledge (and the people) that remind you of the bigger picture. Little by little, you can choose a kinder narrative. We can all move beyond the myths and step into the truth: that we are resilient, we are growing, and we are never as alone – or as broken – as those old stories would have us believe.

“Tear off the mask, your face is glorious.”

-Rumi